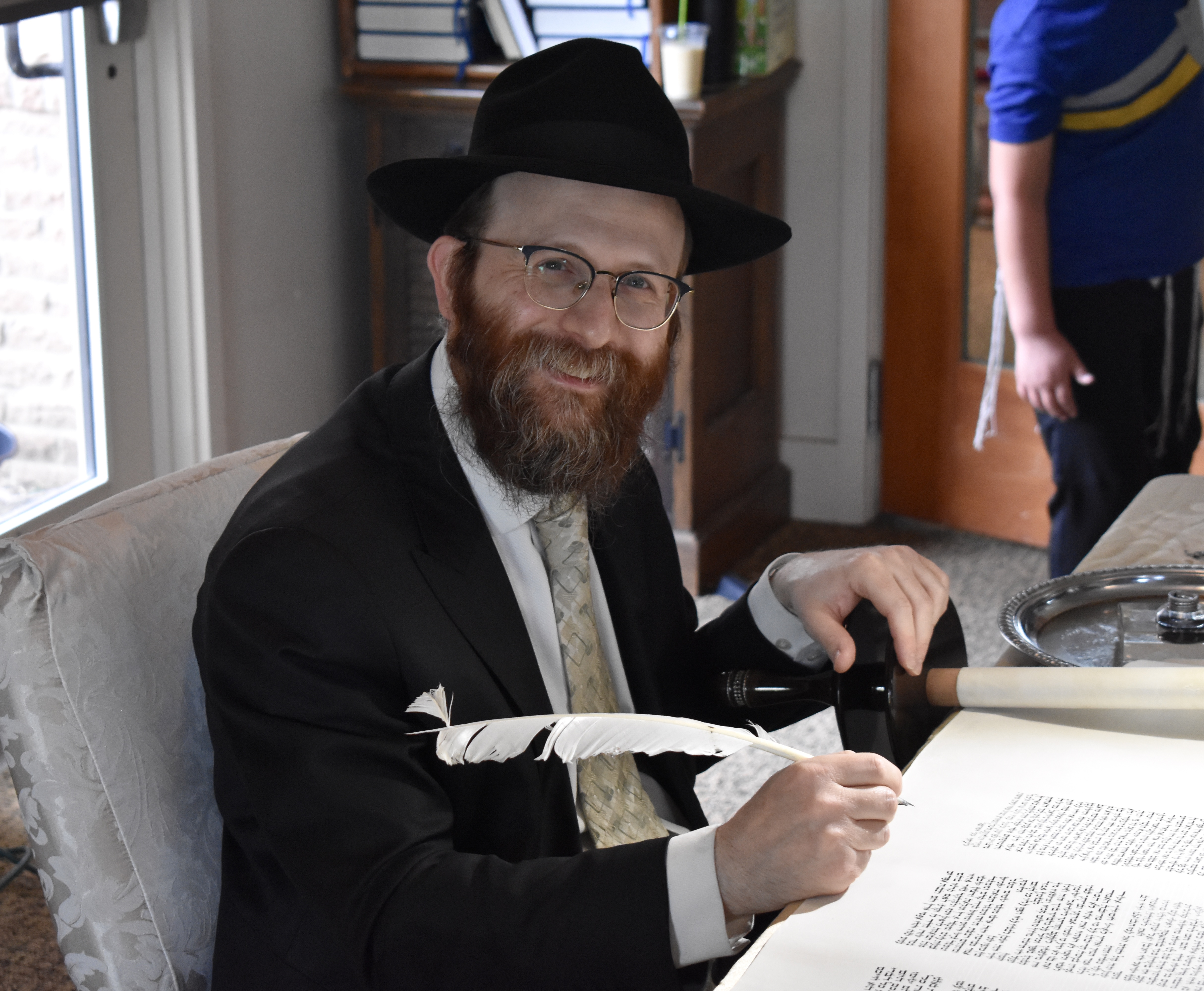

Kosher Torahs, mezuzot and tefillin do not come out of a printer — they are carefully handwritten by soferim (scribes) who must follow detailed laws that go back thousands of years. Overland Park’s Rabbi Berel Sosover is a trained sofer — the only one in the state of Kansas.

In addition to his work as a Jewish studies teacher at Hyman Brand Hebrew Academy (HBHA) and assistant rabbi of Torah Learning Center (TLC), Rabbi Sosover practices safrut (Jewish ritual writing) and is one of a small subset of Jews who are qualified to write Torahs, mezuzot, tefillin and certain religious documents.

“I do work regularly, continuously writing in the summer,” he said. “During the school year, I write less, but I’m always keeping up, always writing.”

Born and raised in the Chabad community in Brooklyn, New York, Rabbi Sosover has been living in the Kansas City area for 18 years. He was invited by Rabbi Benzion and Esther Friedman, executive directors of the TLC, to join them as Chabad emissaries and to teach at HBHA and work with the synagogue.

Rabbi Sosover has been a sofer for about a decade. His interest was first sparked in 2011, during a summer break from HBHA, when he traveled back to New York and encountered his cousin, a sofer who lives in Israel. Rabbi Sosover’s cousin convinced him to take a class to study safrut, beginning with learning to write the Hebrew letters in the proper script.

Inspired and interested in pursuing safrut further, Rabbi Sosover began his full studies in New York, continuing remotely when he returned to Kansas.

In 2013, Rabbi Sosover completed a Megillah from which he would read at HBHA’s Purim festivities. The creation of a Megillah does not require a certified scribe, but it is a learning experience and beneficial practice on the path to becoming a sofer.

Soon after, Rabbi Sosover was certified as a sofer by Vaad Mishmeret Stam, an organization dedicated to ensuring Torahs, mezuzot and tefillin being labeled and sold as kosher are actually kosher. The certification process included learning thousands of intricate laws, practicing religious handwriting thoroughly and ensuring that all safrut is done with intentionality and concentration.

He regularly reviews the laws of safrut due to the sheer number of them — “There are so many thousands upon thousands of laws that one needs to know before [becoming a sofer]… and not every law comes up every day,” he said.

The history of safrut

Jewish law consists of both written and oral parts. The Torah says that the Jewish people are supposed to write mezuzot and tefillin, but it doesn’t give details about how they’re supposed to look. The Oral Law lays the groundwork for those details, including for safrut.

“The Oral Law is there to explain the Written Law,” Rabbi Sosover said. “Moshe received at Mount Sinai the details and taught that over to the Jewish people; that is written in the Talmud. Then later, in the code of Jewish law (Shulchan Aruch) and many other books, [laws] specifically on safrut [were written].”

There are minor differences between certain styles (such as Ashkenazi and Sephardi scripts), but the overarching laws of safrut are universal. Even the utensils and materials used by soferim are described in detail. The parchment, known as klaf, must be from the skin of a kosher animal and prepared specially; the writing device, known as the kulmus, must be a feather from a kosher bird or a reed (Rabbi Sosover uses a turkey quill); and the ink, known as d’yo, must contain a multitude of ingredients including honey and tree sap.

Every aspect of how letters are formed is meticulously laid out; Rabbi Sosover gave the example of the small embellishments (or crowns) on certain letters.

“Certain letters have crowns on them,” Rabbi Sosover said. “It says that Rabbi Akiva, going back to the time of the Mishnah, would study and expound laws — piles and piles of laws — about each one of those crowns. Now, we don’t have those laws; most of that was all lost. But the point is that everything in the Torah, even the crowns of the Torah, are there as parts of the Torah. It’s not some design that we decided… these are essential parts of the writing.”

Soferim sometimes make mistakes, and there are laws regarding what can and cannot be fixed. For example, under no circumstance can G-d’s name be erased, and in most situations, no letter can be created by erasing (removing a ligature from one letter to turn it into another).

There is slightly more leniency regarding fixing a mistake in a Torah than in smaller items like mezuzot and tefillin, but if a mistake is bad enough, the entire work may need to be put into a genizah (repository for worn or damaged sacred documents/ritual objects) and later buried.

Ensuring kosher products

Certification from Vaad Mishmeret Stam helps ensure that the product a sofer is selling is truly kosher.

“We must do [certification] because a lot of people can write, and a lot of people can be artists, but there are many laws that one needs to know before starting to write [as a sofer],” Rabbi Sosover said. “If one does not know the laws, the chances are [the document] is not going to be kosher.”

Rabbi Sosover emphasized the importance of individuals knowing the source of their tefillin and mezuzot and who is selling them. Even synagogue Judaica shops, he said, may unknowingly carry non-kosher products.

“Even to the trained eye,” he said, “sometimes you might see something that looks very nice, but if you don’t know who the scribe is, who the retailer is [or if] they’re only using certified products… it’s very likely that it looks nice, but it’s not actually kosher because it wasn’t written with all the laws that it’s supposed to be written with.”

To ensure that his products are kosher and free of mistakes, Rabbi Sosover sends them to New York to be checked by both a computer — which works well for finding extra or missing letters or words — and another trained sofer who checks the computer’s work and examines finer details.

Over time, parchment and ink can crack, potentially rendering a mezuzah, Torah or tefillin non-kosher. Jewish law says that mezuzot specifically should be checked twice in seven years. Rabbi Sosover said that it’s a good idea to check tefillin too, and that the Lubavitcher Rebbe encouraged people to check their mezuzot every year before Rosh Hashanah.

Celebrating a new Torah

On Monday, Sept. 4, Rabbi Sosover completed the last few lines of a new Torah at TLC. The new Torah, gifted to the congregation by Galit and Alexander Israeli, was dedicated after learning that one of the congregation’s Torahs had a broken letter due to the age of the ink and parchment.

“According to Halacha (Jewish law), all the letters in a Torah must be intact and recognizable,” Rabbi Benzion Friedman, director of the TLC, told The Chronicle ahead of the new Torah’s completion. “With a new Torah, this concern is greatly alleviated, so there is tremendous excitement over the gift. The Israelis have performed a wonderful mitzvah in providing the TLC with this new Torah.”

Community members had the opportunity to sponsor words or letters in the last few lines. By using Rabbi Sosover as an agent, their sponsorship is as if they participated in the creation of that Torah.

When Rabbi Sosover finished, he and all the attendees at TLC participated in a parade with music, singing and dancing. The new Torah was carried around under a canopy, and people carried torches in celebration. After the parade, congregants danced hakafot (circles) around the bimah seven times with the new Torah and the existing Torahs that “welcomed” it.

Rabbi Sosover was also responsible for the completion of KU Chabad’s Unity Torah Scroll in 2015. Then-Kansas Governor Sam Brownback proclaimed the day of its completion “Torah Day.”

In between work at HBHA, Rabbi Sosover continues to work diligently on Torah, mezuzot and tefillin at a dedicated workspace in his home. He lives in Overland Park with his wife, Chanie, and seven children.

Regarding safrut, Rabbi Sosover has one major goal: writing an entire Torah, front to back.

“It’ll take me a very long time… but maybe one day,” he said. “I have an aspiration to do so.”