I’m not saying Lenny Zeskind prevented the Oklahoma City terror bombing of 1995 from taking place in Kansas City, Missouri. But he might have.

Recall that just a couple of years prior to that, Lenny helped to monkey wrench the local Ku Klux Klan leader, Dennis Mahon, in a well-publicized dust-up over a stillborn KKK public-access television program in KC. After that, Mahon slunk off to Oklahoma, where he continued to move in white supremacist circles, including that state’s Elohim City compound, which OKC bomber Timothy McVeigh called a couple of weeks before the attack, perhaps planning to seek refuge there afterward as other high-profile white-wing criminals had done. And we know that McVeigh and his Kansas-based accomplice Terry Nichols considered bombing our downtown Richard Bolling Federal Building.

So it’s not inconceivable that Lenny, through Mahon, helped deflect McVeigh from Kansas City.

It’s just the sort of thing he loved to do with the hard-won, arcane knowledge he had gathered on scuzzy characters like Mahon and fever swamps like Elohim City and the Covenant, the Sword and the Arm of the Lord in southern Missouri that were festering all around us in the late 20th century.

Lenny recognized the threat of white nationalism before almost anyone else, and it was no comfort to him in his later years to see his prescience proven over and over. He risked his life to penetrate white-supremacist networks (they didn’t appreciate being exposed!), and he used that knowledge to serve the Jewish and other targeted communities here and around the world. All without personal aggrandizement — indeed, most often secretly — and with only the purest motives: love for his fellow man and woman.

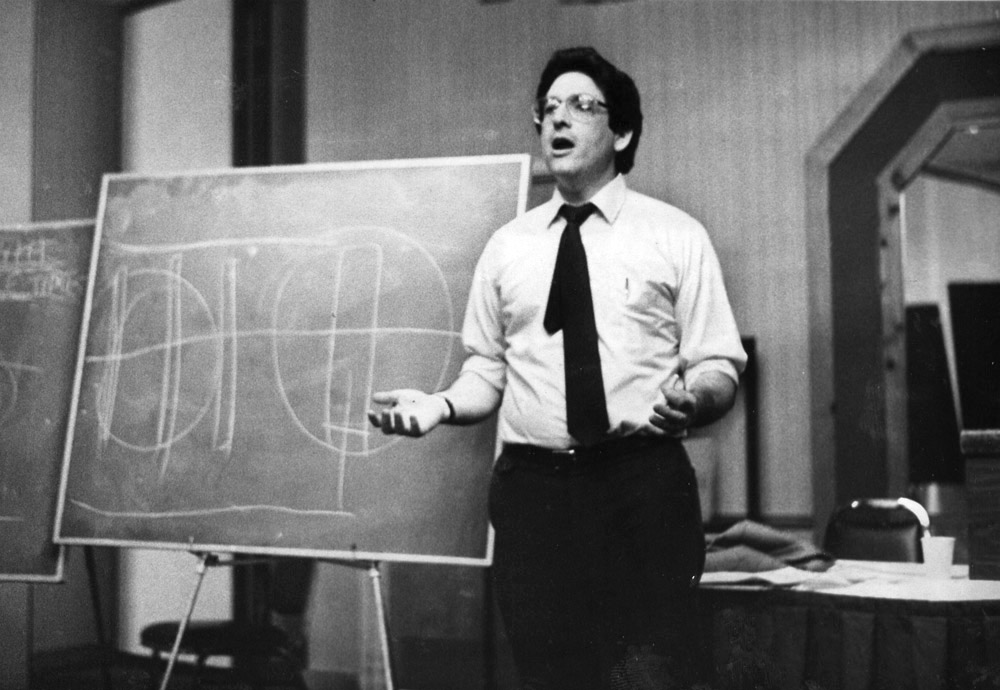

He will be deeply missed in greater Kansas City following his death on April 15 at age 75.

A Baltimore native, Lenny came to Kansas City in the 1970s after dropping out of the University of Kansas. After a series of blue-collar jobs, he began in the 1980s pursuing his life’s work of analyzing the neo-Nazis, reading their publications, attending their meetings, running spies in their midst, liaising with law enforcement, working with anti-Klan groups and so on. The voluminous files he compiled formed the corpus of his magnum opus, “Blood and Politics: The History of the White Nationalist Movement from the Margins to the Mainstream” (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2009).

Lenny was a great friend to me in my years as Jewish Chronicle editor and beyond. His tips led to front-page stories about neo-Nazi booksellers at the Y2K preparedness expo at Bartle Hall and the visit of infamous British Holocaust denier David Irving to give a speech to local supporters.

Likewise, he was a crucial adviser to my mother, Judy Hellman, and the late David Goldstein as they led the Jewish Community Relations Bureau during the 1980s and ‘90s. Lenny and his wife, Carol, helped conceive, advise and support a JCRB “farm crisis” program in 1986-88 that built understanding between the local Jewish community and Kansas farmers who were being targeted with antisemitic propaganda seeking to exploit their economic pain and turn it against Jews.

When another group of neo-Nazis came to town in 2013 for a rally in front of City Hall, Lenny helped the Jewish community organize a counter-rally at Liberty Memorial, avoiding confrontation and promoting unity.

Using the transitive property, as a favorite son, Kansas City’s Jewish community benefited from the respect with which Lenny’s anti-Klan work was held internationally, but especially in the local Black community. He walked the talk.

That’s why he was so deserving of the 1998 “Genius Grant” from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

Rereading the story I wrote for The Chronicle about the grant, I was struck by Lenny’s quote: “We live in a new historical era. The post-World War II glow of victory in the fight against fascism is gone. The lessons we’ve learned as a society from the defeat of Hitlerism are in danger of being unlearned.”

It will be so much harder to continue the fight without him, but it’s the best tribute we can pay.

I can assure you that the anti-fascist, Klanwatching group he formed, the Institute for Research and Education on Human Rights, continues to do great work under his protege, Devin Burghart, so supporting its efforts is a great way to honor Lenny.

Community member Rick Hellman has spent decades in the journalism and communications fields, including serving as editor of The Kansas City Jewish Chronicle throughout the 1990s and 2000s.