The religious rights of women in Israel may have just recently come to the surface of public opinion here in the United States. But women’s rights have long been one of the focuses of acclaimed artist Andi Arnovitz’s work. Arnovitz, who was born in Kansas City and moved to Israel in 1999, spent some time in the area late this summer visiting her parents, Sylvia and Marshall LaVine, and discussing her art.

The religious rights of women in Israel may have just recently come to the surface of public opinion here in the United States. But women’s rights have long been one of the focuses of acclaimed artist Andi Arnovitz’s work. Arnovitz, who was born in Kansas City and moved to Israel in 1999, spent some time in the area late this summer visiting her parents, Sylvia and Marshall LaVine, and discussing her art.

Arnovitz has always been an artist, pointing out that one of her role models was her art teacher at the old Meadowbrook Junior High School. She has high praise for her high school alma mater, Shawnee Mission East, as well.

“I still think Shawnee Mission East’s art program is one of the best high school art programs ever,” she said. “The fact that we did jewelry and ceramics and print making …. That was an incredible education and a phenomenal program.”

Armed with the Bachelor of Fine Arts degree she earned from Washington University in St. Louis in 1981, Arnovitz entered the world of advertising, working for some big-name agencies such as Darcy, MacManus, Masius in Atlanta and Ogilvy and Mather in New York, where she served as art director.

Along the way she met and married David Arnovitz, and following the birth of her third child — the Arnovitzes have five children — she quit the advertising business and started “making art.” She’s made quite a name for herself in Israel, the United States and around the world.

“A lot of what I’m doing now is incredibly labor intensive, so the pieces are very expensive. I would say that I sell regularly, but I’m also now a little less interested in selling and a lot more interested in participating in museum shows,” Arnovitz said.

Over the years Arnovitz has been featured in more than a dozen different articles in such publications as Christian Science Monitor and Tablet magazine. The Arnovitz home, which she and her husband built in Jerusalem and includes a third-floor art studio, has even been featured in The New York Times. In the article Arnovitz described the home as “another art project.”

Arnovitz has exhibited her work in England, the United States, Israel, Spain, Poland, Finland, France, Lithuania, Canada and Bulgaria. She has had many one-woman shows and participated in multiple group shows. Her work is in many private collections in both the United States and in Europe. She is represented in Jerusalem by several galleries and her work is currently featured at three museums: Hebrew Union College in New York, BayCrest in Toronto and the Museum of Art in Ein Harod.

When Arnovitz first moved to Israel, she created a lot of prints about Jerusalem.

“They were these romanticized, graphic collages of things that I thought were particularly seductive about Jerusalem like old buildings and arched windows and pomegranates,” explained the woman who grew up as a Reform Jew and now describes her family as shomrei mitzvot.

Arnovitz’s work now is more often centered on various tensions in Israel that exist within religion, gender and politics.

“The things that I am doing now are not pretty. They are highly conceptual. There is an aesthetic to them, but they are not easy pieces. In the very beginning it was almost like I was trying to convince myself how beautiful this place was I was living in. They were overly romanticized, attractive things to go on the wall. I don’t do that at all now,” Arnovitz said.

A lot of her work has something to do with women’s issues.

“I didn’t start out to do this, but I’m definitely a feminist artist because everything I do is from a woman’s point of view,” she noted.

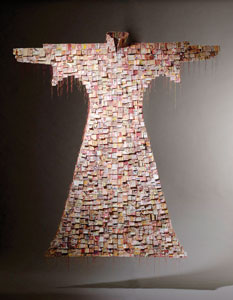

One featuring a woman’s view is a series of coats devoted to agunot, the so-called “chained women.” According to Jewish law, agunot cannot remarry due to their husbands’ refusal to grant a divorce, or inconclusive evidence of a husband’s death. To make these coats, Arnovitz obtained and digitally copied hundreds of ketubot (marriage contracts), and tore them into small pieces. With thread she affixed the fragments onto massive paper coats. The sleeves, hems and collars were sewn shut, and the threads, evidence of her painstaking process, were left hanging, a metaphor for the agunah herself.

“She is completely trapped by this piece of paper. I made the coat out of paper because it’s a piece of paper (her ketubah) that’s wrecked her life and it’s a piece of paper (the get or divorce decree) she’s waiting for,” the artist explained.

She uses a variety of mediums for her art. She uses etching, digital information and various printmaking processes, as well as fabric and thread to create large-scale dimensional paper garments.

Arnovitz uses a lot of fabric and thread in her artwork, and that natural affinity for textiles can be traced back to the days of her youth when she spent time at LaVine’s Fabrics, a shop owned by her father and her grandmother, Sonia LaVine.

“There are threads in almost everything I do. There is a deep love of fiber but I think because I was an art director in advertising I’m very obsessed about ideas and concepts. So when I work I do a lot of double-checking, (determining if) this is the right media to transmit the idea. I don’t automatically go to fabric and I don’t automatically go to paper. I think, ‘which is the most powerful vehicle to carry the idea?’ ”

“Right now I am a little bit obsessed with the idea of mending in terms of repair and pushing that concept in terms of repairing realities, like political situations,” she continued.

Many of her works feature textiles and papers that she has wound, wrapped and tied. She believes those methods are quintessential Jewish acts.

“I think when you do a close investigation of Jewish ritual you will find those motions repeated over and over again. For example we roll and wind the Torah. We bind the Torah. We braid challot. We wrap tefillin. We draw the Shabbat lights toward our eyes in this motion three times,” she explained. “Even the chevra kadisha (where she was a member in Atlanta) has a very ritualized way of tying knots on a shroud. To me, a lot of what I do in my art is something that is repeated over and over again in Jewish ritual.”

When she originally went to Jerusalem in 1999, Arnovitz thought it was simply for a sabbatical. But she loves living there.

“I would say for me the most compelling thing is that we made incredible friends. For some reason Jerusalem just has incredible people, idealistic people, professors and scholars and authors and poets and artists. There’s this enormous concentration of talent in Jerusalem. We just have really interesting and great friends, and their kids,” she said.