Sidonia Perlstein survived the Holocaust to become a talented designer and seamstress. But when Perlstein died on Mother’s Day six years ago at the age of 93, she was still a mystery to the daughter she had raised alone in western Massachusetts.

Sidonia Perlstein survived the Holocaust to become a talented designer and seamstress. But when Perlstein died on Mother’s Day six years ago at the age of 93, she was still a mystery to the daughter she had raised alone in western Massachusetts.

“My real mother was someone I never truly knew,” said Hanna Perlstein Marcus.

But Sidonia’s death only made Marcus more determined to understand her mother and seek out the father about whom she would never speak.

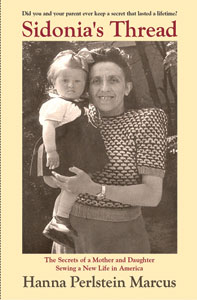

Marcus recounts what she learned in her memoir, “Sidonia’s Thread: The Secrets of a Mother and Daughter Sewing a New Thread in America.” It is available online at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

“Piecing together her story showed me a mother who was a stronger, more resilient and courageous person than I ever thought,” said Marcus, who is 64.

Their story begins in 1947 in a displaced persons camp near the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in northwest Germany. In her mid-30s, an unwed Sidonia gave birth to a daughter she affectionately called “Hanele” (little Hanna). Two years later, the two immigrated to the United States. Since they had no American relatives to sponsor them, the American Joint Distribution Committee randomly assigned them to Springfield, Mass.

The author has connections to Kansas City. Steve Rothstein and Ann Rothstein Cromer (now Chana Cromer of Jerusalem), are two of her only cousins in the entire world.

“Steve’s mother, Olga, and my mother were first cousins since their mothers were sisters. They came from the Tokaj-Hegyalja wine-producing region in Northeastern Hungary. Olga, her brother Ference, who returned to Hungary after being liberated, and my mother were among less than a handful of that extended family who survived the Holocaust. When they arrived in America, Olga and her family settled in Kansas City,” Marcus said.

Marcus said Sidonia was blessed with a self-taught talent for sewing and a flair for fashion.

“She was a fashionista and a great admirer of Jackie Kennedy. I’m tall and thin, so I was her perfect model.”

Although mother and daughter were close, Marcus felt that her mother wanted to keep part of herself at a distance. For example when she was 6, she asked about her father.

Her mother’s “response was cold, and she was unwilling to talk,” Marcus said. “I never asked again.”

Both mother and daughter always wore clothes designed and made by Sidonia.

“For the most part, I realized the clothes she made were stunning. I was wearing couturier clothes when I was 13 years old,” Marcus said.

Sidonia went from working in a dress factory to becoming a foreman and finally opening her own business as a fashion designer and seamstress. One grateful customer gave her “Coats and Clark’s Sewing Book: Newest Methods from A to Z” (1967), the only sewing book Sidonia ever owned. She never opened it, but the book always sat on a table in her sewing room.

Marcus went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in psychology at UMass.-Amherst. Wearing her mother’s designs, she was voted one of the best-dressed women on campus.

At the University of Connecticut, she received master’s degrees in counseling and social work. As a licensed clinical social worker, she embarked on a career in social work and public sector human services. After marrying in 1969, she had two children, Brenda and Stephen, and settled in Vernon, Conn.

In the mid-1980s, Marcus and her daughter accompanied Sidonia to her hometown in Hungary.

“When my mother and her family were deported, they always thought they would be back,” Marcus said. “They had treasures hidden for safekeeping. We were searching to see if there were mementoes of the family I never knew.”

They didn’t find anything, but Hungary reignited Marcus’ interest in her mother’s past.

“The trip was a turning point. My feelings changed, and I wanted to write about it,” she said.

In 1998, while helping the then 86-year-old move into senior housing, Marcus looked inside her mother’s nightstand and found it filled with photos and with papers and letters, in Hungarian, Yiddish and German.

“I took them without her knowing it, and had them translated,” Marcus said. “They revealed unexpected surprises” — including that Marcus’ father was much younger than her mother and didn’t want to commit to marrying an older woman. There was enough information for Marcus to trace him to his home in Israel.

“When I finally called my father, he was neither cordial nor receptive to my requests to arrange a meeting between us, having never revealed my existence to his family,” said Marcus. “My childhood dreams of finding a father who would welcome me with open arms were shattered. Although I eventually met the daughter he had later in his life, it never turned into a lasting relationship.”

Drawing on the papers from the nightstand, the trip to Hungary and her childhood memories, Marcus assembled a picture of her mother.

Sidonia was a “content and somewhat sheltered woman who came from a close-knit, large immediate and extended family, all lost in the Holocaust,” said Marcus. “She was a changed woman after the war, very insular, solitary and reclusive — unable to reveal how her child was conceived, her correct age and why she behaved in such a withdrawn manner.”

Sidonia and her sister Laura were interned at Auschwitz, Dachau and Bergen-Belsen. Laura died of typhus only two months before the liberation of Bergen Belsen in April, 1945.

“In Dachau, during a roll call, the officer in charge asked if anyone could sew,” Marcus said. “My mother must have shouted louder than any other woman with her hand raised because she was chosen to work in the camp’s office. She sewed ripped seams, buttons, and replaced zippers for the soldiers and office staff during her last few weeks in Dachau. Because her leg was broken just a day before [that roll call], I have always thought that her sewing skill actually saved her life during the Holocaust.”

Following Sidonia’s death in 2006, Marcus began to think about writing the book. “My mother went to her death without knowing I had uncovered these treasures in her nightstand,” Marcus said. “She never told me secrets. We were keeping secrets from each other.”

Originally, Marcus planned do genealogical research by finding people who knew her mother in Hungary or in the DP camp. She succeeded in contacting some of them, but nearly all were reluctant to talk.

“So I decided to write mainly from memory,” Marcus said. “My research was not scholarly. This is a very personal story.”

As she began to write, Marcus remembered the sewing book the customer had given her mother. With permission from the Coats and Clark Company, Marcus used titles and excerpts from the book to serve as the “thread” to tie her own book together.

“ ‘Sidonia’s Thread’ is really about Sidonia. I am the facilitator to tell her story,” said Marcus.

Parts of this article were originally published in The Jewish Advocate of Boston.