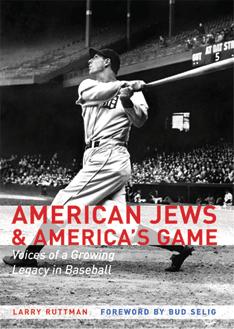

“American Jews and America’s Game: Voices of a Growing Legacy in Baseball” by Larry Ruttman (University of Nebraska Press 2013)

“For American Jews, baseball has been the tent of Abraham, offering many travelers entrance into both American life and Jewish self-identification.” Thus Larry Ruttman writes in his introduction to

“For American Jews, baseball has been the tent of Abraham, offering many travelers entrance into both American life and Jewish self-identification.” Thus Larry Ruttman writes in his introduction to

his collection of portraits of various Jews involved in the national pastime, a book whose very size appears to belie the gag from the film “Airplane,” which describes a book about Jewish sports heroes as a small pamphlet.

As one might surmise, however, Ruttman does not focus exclusively on those who have played the game. Many of the most significant figures he portrays are those involved in baseball off the field, such as sportswriters, and executives like Commissioner Bud Selig. One might even accuse him of padding when he interviews Jewish celebrities who happen to be avid sports fans, such as Congressman Barney Frank, or the spectator who was guilty of fan interference in the 1996 playoffs. Also, one could question how “Jewish” some of the players interviewed really are. Brad Ausmus and Ian Kinsler, for example, though both of Jewish parentage, admit to having no real background or affiliation with the Jewish community.

With one exception, all of the people profiled in the book were interviewed personally by the author. The exception is the late Hank Greenberg, who was too important to exclude, and who is profiled through personal interviews with his friends and family.

There have been some major Jewish stars over the years, including Greenberg, Ken Holtzman, Al Rosen, and, of course, Sandy Koufax. Two members of the All American Girls baseball league — a league that was virtually forgotten until it was commemorated in the film “A League of Their Own” — also make an appearance. The one player whose Jewish identity will probably be a surprise to most readers is Elliott Maddox, an African-American Jew by choice. Given the number of players who admit that Jewishness is of little consequence in their lives, it is inspiring to hear from someone for whom Jewish identity is so central.

Perhaps more essential to the development of the game than any of these players, however, are the two major figures who guided the Players’ Association: Marvin Miller and Donald Fehr (who has roots in Kansas City). Though they have been reviled by some, Ruttman treats them as heroes who brought a sense of fairness to the game. He quotes sportscaster Red Barber, who called Miller, along with Jackie Robinson and Babe Ruth, one of the two or three most important people in baseball history.

While there is a lot of interesting material in this book, I sometimes found the interviews a bit irrelevant. Ruttman asks a number of the players about the future of Judaism in America. Given that this is not their area of expertise, do I really care what they think?

Some sports books transcend their subject matter. Roger Kahn’s “The Boys of Summer” and Joe Posnanski’s “The Soul of Baseball” (both, coincidentally, written by Jews) are books that for different reasons reach out to a wider audience. “American Jews and America’s Game” is not in this category. Its appeal is probably limited to Jewish baseball fanatics, and it might make a nice gift if you have someone in your family who fits that description.

Stuart Lewis holds a doctoral degree in English from the University of Colorado. He writes from Prairie Village.