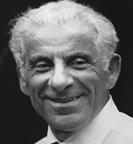

Isak Federman came to Kansas City in 1946, the only member of his family to have survived the Holocaust. He was a successful businessman, a loving parent and a generous supporter of the Kansas City Jewish community. He was a character, a dramatic and humorous storyteller who could take over a room and make friends instantly. He died on Sept. 9, 2016, at the age of 94.

Isak was born on March 14, 1922, in Wolbrom, Poland, the third child of Boruch and Ruchla Biala Federman. His father died before Isak was a year old, and his mother eventually remarried Herschel Kalisz with whom she had a fourth child. Encouraged by his mother and stepfather, he left home at the age of 13 to study at a Yeshiva (a school for Jewish boys), but returned home in the summer of 1939 amid rumors of a German invasion. After his village was occupied he was picked up on the street by the German SS in the fall of 1939, and ordered to help build a forced labor camp nearby. Eventually, he was forced to do slave labor in 18 camps, including Rzeszow, Plaszow, Flossenberg and Sachsenhausen. He built roads and barracks, worked in salt mines, and “pretended” to operate a lathe machine. He was also forced to clean up rubble from the German invasion of Russia, and later, he and other prisoners were marched into Berlin during bombing raids and forced to clear rubble there as well. In 1944, he was shot in the head and wrist while escaping from the concentration camp at Bergen Belsen, near Hamburg, and survived in the forest for several days before being captured. He was liberated by the British Army on May 3, 1945, weighing about 80 pounds, and sick with typhus.

After Isak had spent about six weeks in an army field hospital, he went back to Bergen Belsen, where a displaced persons camp had been established, in hopes of finding information about his family. He found no surviving family members, but he met Anna (Chana) Warshawski, who remained lovingly devoted to him for the rest of his life, as he was to her. In December 1945, he heard a radio translation of a speech in which President Truman announced that 100,000 displaced persons would be allowed to immigrate to the United States. He encouraged Anna and her surviving family members to apply. In June 1946, they traveled to New York under the sponsorship of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. When they arrived, the Joint representative suggested they move to Kansas City. In Yiddish, Isak asked him if Kansas City was in America; upon being told that it was, he said that they would go. That September, he and Anna, now Ann, were married, the first survivors to do so in the Kansas City area. Five hundred “strangers” attended their wedding, and they were embraced by the Jewish community in Kansas City. They were immediately invited to join Kerem Israel Synagogue, now Kehilath Israel. Over the years, Isak and Ann made a number of lifelong friends with whom they shared a commitment to Kehilath Israel. Isak served the synagogue in a number of ways, including as its president. He was actively involved in B’nai Brith and Jewish Federation of Kansas City, and was both a Mason and a Shriner. While he referred to himself as a “newcomer” (“green-ah” in Yiddish) he was bold and self-confident, a salesman who was hard to resist, genuinely liked by his customers, and a hard worker. In 1948, while still learning the English language, he co-founded Superior Upholstered Furniture Company. He sold that company in 1976 and after being retired “for a weekend” became restless and started K.C. Textile Company, which he eventually sold in 1996. While he would point out that his secular education stopped after seven grades, he was an astute businessman, a dealmaker whose handshake was his bond. Indeed, he was a founding director of Lenexa National Bank, and was the board chair who led the negotiation of its sale to Commerce Bank.

In 1993, along with his good friend Jack Mandelbaum, he co-founded the Midwest Center for Holocaust Education, which teaches the history of the Holocaust as a means to counter indifference, intolerance and genocide. Isak had always been reluctant to discuss his wartime experiences; despite that, he decided to share those experiences to help raise funds for MCHE. None of his friends were spared his pitch, as he and Jack worked to help build and finance an organization that continues to serve the entire community. He loved reading about and discussing current events and history, attending sporting events, and traveling with Ann. He was a patriot, proud to be a citizen of the United States and grateful to Kansas City for welcoming him when he had no home to return to.

In addition to his beloved wife Ann, he is survived by three children, Rachel Altman (Avrom), Arthur Federman (Diane), and Lorie Federman: by five grandchildren (Rebekah Altman, Audrey Federman, Carla Federman, Elijah Knight and Maya Knight); and by seven great-grandchildren. The family thanks the staff of Suites 2 and 3 at Village Shalom and that of Kansas City Hospice for their devoted care of Isak during the last years of his life. Special thanks to Sonia Warshawski for her love and support of Ann.

Funeral services were held Sept. 11 at Louis Memorial Chapel; burial followed at Kehilath Israel Blue Ridge Cemetery. The family requests no flowers and suggests contributions to the Midwest Center for Holocaust Education (mchekc.org), 5801 W. 115th Street, Suite 106, Overland Park, Kansas 66211, Kehilath Israel Synagogue (kisyn.org), 10501 Conser, Overland Park, Kansas 66212, or Jewish Federation of Greater Kansas City (jewishkc.org), 5801 W. 115th Street, Suite 201, Overland Park, Kansas 66211.

Online condolences may be left for the family at www.louismemorialchapel.com.

Arrangements by The Louis Memorial Chapel, 816-361-5211.